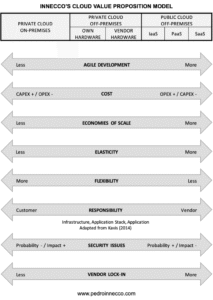

When I first developed the Cloud Value Proposition Model during my MSc dissertation, the goal was simple: create a tool to help organisations evaluate different cloud deployment options in a strategic, structured way. Nearly a decade later, the cloud landscape has evolved dramatically. Hybrid models are the norm. Cloud-native tooling has exploded. And business decision-making is far more cloud-literate. So how well does the model hold up in 2025?

In this post, I revisit the model critically: what it got right, what no longer applies, and what I’d change if I were building it today.

The model mapped deployment types (from on-prem to SaaS) against key dimensions such as cost, agility, responsibility, and vendor lock-in.

What Still Holds

Strategic Trade-Offs Still Matter

The model was built on the idea that every deployment choice comes with trade-offs. That’s as true today as it was then. Agility often comes at the cost of control. Flexibility might come with complexity. These tensions haven’t gone away; they’ve simply shifted.

It’s Still a Strong Communication Tool

Even now, organisations struggle to align business, IT, and security stakeholders around cloud decisions. The model remains useful as a way to surface hidden assumptions and make those conversations more productive.

What Has Shifted

1. The Spectrum Is Blurred

In the original model, deployment types moved linearly from Private Cloud to SaaS. But in today’s world of hybrid, multi-cloud, containers, and edge computing, those boundaries are more fluid. You’re no longer choosing one model over another—you’re composing them.

2. Elasticity Isn’t Cloud’s Exclusive Advantage

When I first wrote the model, on-prem infrastructure was relatively static. That’s changed. With hyperconverged infrastructure, infrastructure-as-code, and hybrid tools like Azure Stack or AWS Outposts, elasticity is no longer the sole domain of the cloud.

3. Flexibility Has Flattened

Originally, the assumption was: the further right you go (towards SaaS), the less flexibility you have. That was largely true in 2015. But now, with the vast number of APIs, cloud-native services, and platform tools, you can build just about anything in the cloud.

Yes, SaaS and PaaS still limit you when a feature isn’t exposed. But those are now exceptions, not the rule. Flexibility isn’t a clean gradient anymore. And when it is limited, it’s often for economic—not technical—reasons.

Which brings us to…

4. The Rise of Granularisation (a.k.a. Enshitification)

Cloud vendors have become experts in unbundling functionality. Want security monitoring? That’s a separate SKU. Want long-term log retention? Pay extra. Want full forensic visibility? Enable another paid tier.

In theory, this gives you choice. In practice, it fragments your architecture, obscures cost predictability, and shifts responsibility back to you. Worse, when things go wrong, you’re often told: “You didn’t enable the right logging tier” or “That data has expired.”

The model didn’t account for this. Responsibility and control aren’t just technical anymore—they’re commercial.

5. Security Risk Is Now Operational, Not Just Technical

The model made a valid distinction: public cloud is a bigger target, but better defended. That still holds. But it missed a now-critical dimension: support and visibility gaps.

Modern cloud security isn’t just about protecting systems. It’s about having the right telemetry, logs, and alerting in place—and paying for them. Without that, you’re effectively blind. In 2025, security risk is shaped as much by how your services are licensed and configured as by their underlying defences.

6. Lock-In Is Less About Infrastructure, More About Velocity

Lock-in used to mean vendor dependence. Now it often means feature dependence. Teams adopt proprietary PaaS features or managed AI services that dramatically speed up delivery—and knowingly embrace lock-in in exchange for velocity. This is a conscious trade-off, but the model presented lock-in only as a risk, not as a strategic lever.

Like flexibility, lock-in today is often a conscious trade-off—a decision to prioritise velocity over optionality.

What the Model Doesn’t Cover—and Wasn’t Meant To

Since I built the model, the strategic landscape has expanded. Today’s cloud decisions also involve factors like:

- Compliance complexity

- AI enablement

- Sustainability goals

- Observability tooling

These aren’t easily plotted on a spectrum from on-prem to SaaS. They’re not about the deployment model itself—they’re about how you design, implement, and govern whatever model you choose. Rather than force them into the framework, I treat them as cross-cutting concerns that deserve their own analysis.

Would I Build the Same Model Today?

Not exactly. I wouldn’t discard it—it still has value. But I would flatten the spectrum, reframe some dimensions, and clearly flag that the “trade-offs” aren’t evenly spaced. The model was never about scoring—it was always about framing the right strategic conversation. That purpose still holds, even if the spectrum itself has flattened.

I would also be more explicit that in many cases, the right deployment model isn’t one point on the spectrum—it’s a deliberate combination of models.

Final Thoughts

The Cloud Value Proposition Model captured a specific moment in the evolution of cloud thinking. It simplified a complex space in a way that made it easier to navigate.

But the cloud has moved on. What were once technical constraints are now economic ones. What seemed like vendor responsibilities are increasingly ours. And what felt like a linear journey now resembles a multidimensional map.

The model still serves. But it needs context—and it deserves critique. Hopefully, this article offers both.